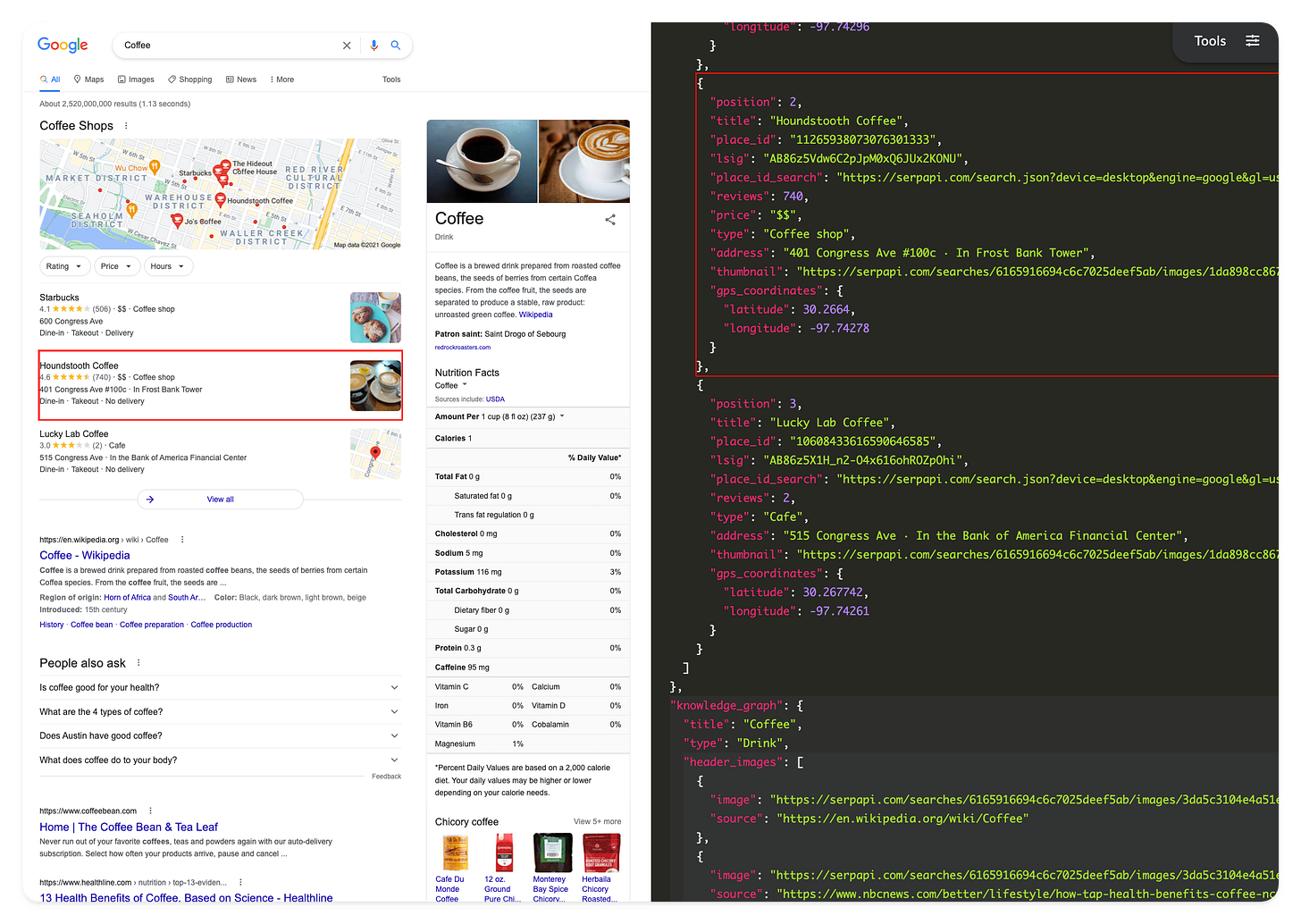

1) 🔌 Get search engine data through APIs

This idea is provided by today’s sponsor, SerpApi!

This week I am happy to promote SerpApi, which scrapes public data from Google, Bing, Amazon and many other top search engines.

You can use their fast and easy APIs to:

🔍 Get real time search results data

🌐 Leverage IPs across the world for localized results

📑 Use JSON search results data the way you want

If you want to try their APIs, you get 250 free monthly searches with every new account

2) 🤖 We need to avoid AI bottlenecks

When it comes to AI adoption in software engineering, most of the attention online is focused on coding.

Coding matters, but it is only one step of the development process. If we improve productivity there (still unproven at this point, btw), we need to lift the other steps too, or we’ll just bottleneck ourselves elsewhere: on code reviews, or product requirements, QA, and so on.

For this reason, recently we have focused on exploring how AI changes other parts of software engineering, outside of pure coding, and we have put together a streak of articles on this, co-written with some of the world’s best experts.

Here are a few:

Each of these articles starts from first principles, includes real-world playbooks, and also tries to think where the puck is going, other than where it is today.

3) ✈️ Translate impact across altitudes

There is a lot of advice online about managing up that, to me, feels overly tactical. Not to say it doesn’t work, but some people apply it verbatim, without stopping to think why.

The reason why managing up even exists, as a topic, is that you and your manager operate on different contexts, which lead you to speak different languages.

So, effective managing up is largely about translating what you do into your manager’s language, mapping your actions, concerns, and outcomes, into theirs.

This usually means moving stuff through different levels of abstraction, or altitudes. Let’s make an example and look at three levels:

🛰️ Strategic (30,000 ft) — the big roadmap connected to the company vision.

🛩️ Tactical (10,000 ft) — the quarterly projects.

🚗 Operational (ground) — the daily/weekly progress.

As an engineer, let’s say you work on some tech debt to improve the reliability of software. That’s ground level. Your manager, instead, may care about how this speeds up the delivery of the quarter initiatives. Your manager’s manager, e.g. the director, may not care about the individual debt items, but more about the process to keep debt in check as a strategic way to retain agility.

The way you speak to these people is wildly different.

Of course, as an engineer, you are not talking with a director about fixing this or that abstraction: that’s what you say to your manager. But your manager will (should?) think in systems and bucket that conversation into the higher level topic of how much time your team spends on maintenance & how this helps productivity. The director then will take that and reflect on the engineering strategy for the department.

So, for any item you report to your manager, the question you should ask yourself is: why should my manager care about this? And, more subtly: what does my manager care about this?

We wrote a full guide about managing up 👇

4) 🧩 Systems thinking everywhere

Exactly one year ago I read An Elegant Puzzle, by Will Larson, on the community book club.

It is the best book I ever read about engineering management, and the reason comes down to one thing: systems thinking. This is a wildly overused term, but Will gives a very precise definition for it.

Systems are combinations of stocks and flows:

🧱 Stocks — are accumulations of resources.

🔀 Flows — are streams that make stocks increase (inflows) or decrease (outflows).

This looks extremely simple and, in fact, through the use of diagrams, it turns systems into equally simple boxes and arrows.

Simple, though, doesn’t mean vague — on the contrary, stocks and flows are precise ideas that, applied well, can model infinitely sophisticated situations.

One of the examples provided is about DORA metrics. The four metrics are flows that impact their respective stocks, and together model the software delivery process as a clear, predictable system (see picture).

Now, thinking at your dev process as a system is still intuitive, or at least it should be, to managers and engineers who have been in the industry for more than a few years.

The main virtue of An Elegant Puzzle, though, is that it applies this line of thinking to everything.

It addresses otherwise nebulous themes like team organization, culture, hiring, or hypergrowth, by uncovering their inner logic and creating mini frameworks that always feel grounded and actionable.

This is extraordinarily useful. In Will’s own words 👇

Once you start thinking about systems, you’ll find it’s hard to stop. Pretty much any difficult problem is worth trying to represent as a system, and even without numbers plugged in I find them powerful thinking aids.

So, “An Elegant Puzzle” may look like an obscure title for an engineering management book, but it all makes sense when you understand Will’s approach to problems. Engineering management’s challenges are explained as a series of puzzles which you have to solve by creating systems for them.

You can find our summary and review of the book below 👇

And that’s it for today! If you are finding this newsletter valuable, consider doing any of these:

1) 🔒 Subscribe to the full version — if you aren’t already, consider becoming a paid subscriber. 1700+ engineers and managers have joined already! Learn more about the benefits of the paid plan here.

2) 📣 Advertise with us — we are always looking for great products that we can recommend to our readers. If you are interested in reaching an audience of tech executives, decision-makers, and engineers, you may want to advertise with us 👇

If you have any comments or feedback, just respond to this email!

I wish you a great week! ☀️

Luca