Convergence, mobile fragmentation, brain systems, and intentional debt 💡

Monday Ideas — Edition #166

1) ➡️ Converge projects intentionally

This idea is brought to you by this week’s sponsor, Shopify!

Last month we covered how Shopify executes his massive Editions twice a year. Out of this process, one of the parts that stuck the most with me is the convergence ritual.

This is a dedicated, time-boxed period before the launch where teams stop building new features and focus entirely on integration and quality. The goal is to move from a collection of siloed features to a single, seamless product experience.

During Convergence, teams are forced to simulate the end-to-end user journey: a team that builds a new API doesn't just test the API — they have to use it to build a complete application, exactly as a third-party developer would. This uncovers friction points, integration gaps, and awkward workflows that would be invisible otherwise.

Overall, this is a mechanism for:

Ensuring the final product is more than the sum of its parts

Creating a shared sense of ownership across the company, avoiding silos

Ensuring that when an Edition ships, it truly works as a cohesive whole

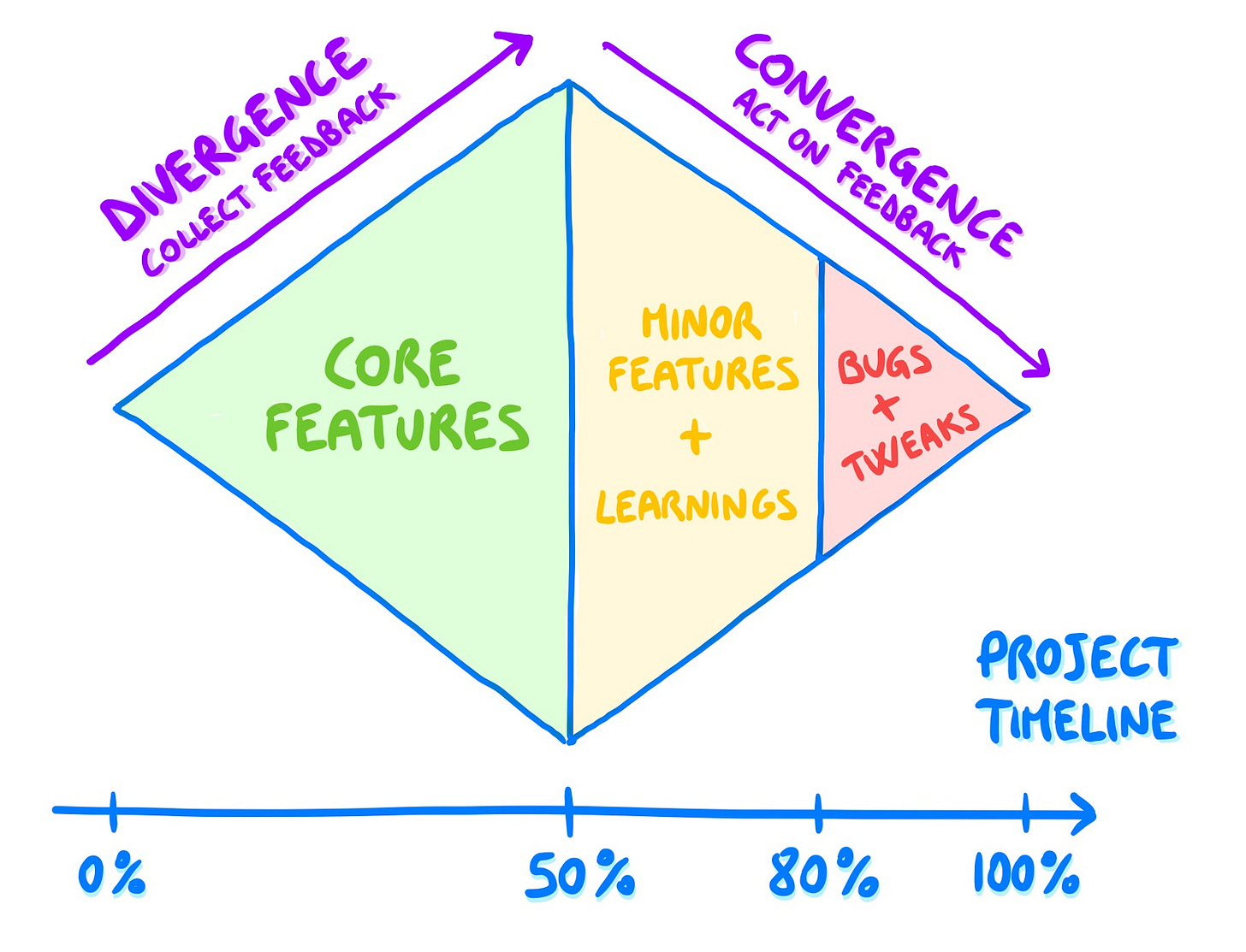

Personally, I am a fan of splitting long projects into divergence + convergence stages — it’s a great way to set the right trajectory and ensure on-time delivery 👇

At the beginning you collect feedback and make sure you are going in the right direction (divergence), and in later stages you converge to a valuable outcome by incorporating feedback, reducing scope, and fixing bugs.

You can find the full article below 👇

2) 📱 What is mobile fragmentation?!

I always feel that non-mobile developers do not fully appreciate the sheer complexity involved in creating mobile apps.

A good chunk of such complexity is brought in by what we call mobile fragmentation — the diversity of hardware and software across the millions of devices your application might encounter in the wild.

Mobile diversity is particularly awful for developers because it is multi-dimensional:

📱Device manufacturers (the who) — from the big players like Apple and Samsung, to the long tail of Xiaomi, Oppo, OnePlus, and the countless regional champions. Each comes with its own hardware quirks, custom Android skins, and unique interpretations of how Android should behave.

📋 Operating systems & versions (the what & when) — you need to account for multiple major versions active concurrently. Update rollouts lead to notorious lags, and some devices never get updated beyond a certain point. This is true for both iOS and Android, with Android being typically much worse.

📏 Screen sizes & resolutions (the where) — today’s smartphones range from compact screens, to phablets, foldables, and tablets: the range is vast. Other than physical size, you may also need to account for pixel density, aspect ratios, and newer features like dynamic refresh rates or screen cutouts (notches, punch-holes), which can all wreak havoc on your UI if not handled gracefully.

⚙️ Hardware differences (the how) — beneath the glass, there's even more: processors, memory constraints, GPUs, and sensors, which may or may not make a difference in how your app behaves.

Accounting for every permutation is impossible, so teams develop strategies based on user distribution, business goals, product stage, and more.

We tried to navigate all of this in the guide we wrote with the guys at BrowserStack back in May👇

3) 🧠 System 1 vs System 2

One of the latest books we have read in our book club is Thinking, Fast & Slow, by Daniel Kahneman.

The book is a masterclass in understanding how our minds work, and especially our hidden biases.

Kahneman's central thesis revolves around two modes of thought: System 1 and System 2.

1️⃣ System 1 — is fast, intuitive, and emotional. It operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.

2️⃣ System 2 — on the other hand, is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. It allocates attention to effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations.

What's surprising — and somewhat unsettling — is how much we rely on System 1, even when we think we're being logical and methodical. We often pride ourselves on our analytical abilities (especially in engineering 🫠), but Kahneman shows that we're far more inclined to make quick, intuitive judgments.

The main problem is that we don’t have a reliable way to figure out when to engage System 2—the analytical side—vs accepting the quick answer provided by System 1.

This is perfectly displayed in the famous bat and ball problem:

"A bat and ball cost $1.10. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

Most people answer 10 cents, which is System 1 stuff. The correct answer (5 cents) would require engaging System 2, but we usually accept the quick answer because it looks good.

This reminded me of chess. During lunch I often watch Hikaru videos, where he often talks about the problem of knowing when to spend your time. Modern chess has shifted more and more towards shorter time controls (e.g. 10-minute games), which means players spend little time, on average, on every move. What’s interesting, especially in grandmaster games, is that players do not spend a similar amount of time on every move — they blitz most of them (i.e. few seconds) and spend long chunks of several minutes on a few crucial ones.

Blitz moves are System 1—quick judgment and pattern-matching—while the long ones are when players engage their analytical brains.

Knowing when it is worth spending more time on a move—i.e. when to engage System 2 vs when to trust intuition—is a crucial quality that separates outstanding players from the good ones.

Similarly, in real life, we need to blitz most decisions because System 2 is 1) slow, and 2) extremely costly, while System 1 is basically free. But we can still create good strategies to fight our biases and give System 1 less leeway.

You can find our full summary + review of the book below 👇

4) 🎒 Does intentional tech debt really exist?

When it comes to startups and fast growing products, you may hear about taking on debt intentionally, as the result of prioritizing speed and growth over engineering quality.

Regardless of whether this would make for a good strategy, in my experience, debt is most often inevitable rather than intentional. Fast growth, in fact, naturally leads to technical debt, because when the product changes at a fast rate, your engineering abstractions get invalidated equally fast.

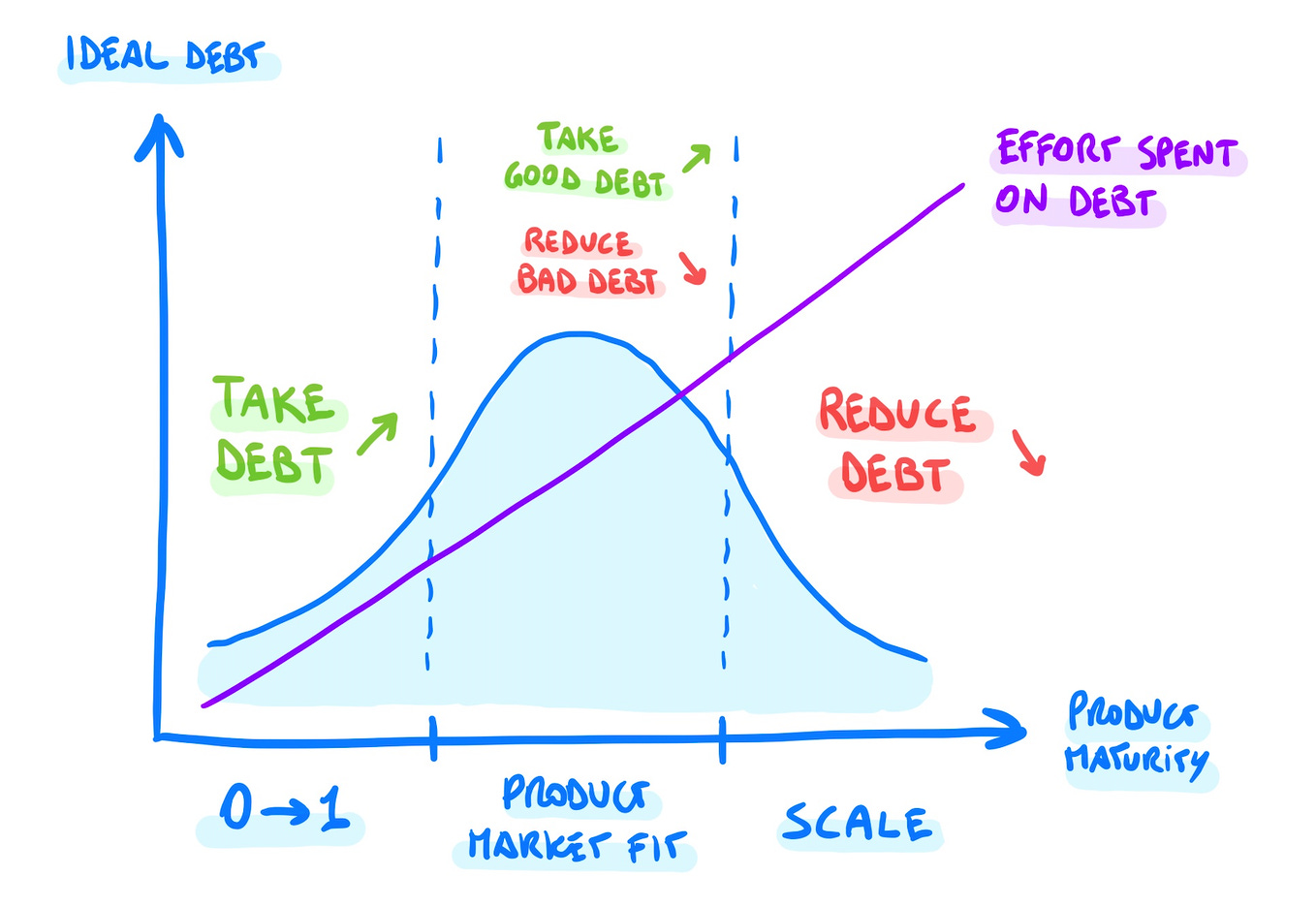

Such volatility, though, changes with the maturity of your product. For the sake of simplicity, let’s consider three stages:

🐣 0 to 1 — you start building a product from scratch, with a set of initial assumptions.

📏 Product Market Fit — you figure out what works, double down on it, and scrap the rest.

📈 Scale — you grow your business predictably and harden your tech.

The earlier you are on this scale, the more your product needs to move fast, and the more leverage you get by accruing debt.

The later you are on the scale, the more debt becomes a drag that prevents your product from growing. Your scale is such that you get the most leverage by repaying debt.

For early stage startups it might be inevitable (and even healthy) to accumulate debt early on. At the same time, though, you should create processes to help repay debt from the very beginning.

You can find our full (and long!) guide on managing technical debt below 👇

And that’s it for today! If you are finding this newsletter valuable, consider doing any of these:

1) 🔒 Subscribe to the full version — if you aren’t already, consider becoming a paid subscriber. 1700+ engineers and managers have joined already! Learn more about the benefits of the paid plan here.

2) 📣 Advertise with us — we are always looking for great products that we can recommend to our readers. If you are interested in reaching an audience of tech executives, decision-makers, and engineers, you may want to advertise with us 👇

If you have any comments or feedback, just respond to this email!

I wish you a great week! ☀️

Luca