Whenever some new tech comes in, there is a period of time in which excitement about the future charges ahead with respect to reality.

The more the excitement, the wider the gap.

With AI, it feels this has been the case for at least the last couple of years, to the point that it even earned its own name: the gen AI paradox.

In June, McKinsey reported that:

Nearly eight in ten companies have deployed generative AI in some form, but roughly the same percentage report no material impact.

Also, 90% of function-specific AI use cases remain stuck in pilot mode.

The answer to these lukewarm results is supposed to be… agents. The thing that turns experiments into impact.

And yet, for most teams, the story is repeating itself. A Gartner poll from this year found that only 15% of tech leaders are actually deploying somewhat autonomous agents, and, from my anecdotal conversations, I confirm this sentiment.

By now, most of us have probably seen more agent demos than we can count. Agents that book flights, write code, handle customer support, or else. Every demo looks flawless — but when you try to put the same thing in production, it falls apart.

So what’s going on?

I have spoken with a lot of teams over the past months, and I believe the gap is not about intelligence. Today’s models are remarkably capable. The gap is about everything else: reliability, infrastructure, and the whole system that needs to be put in place around models.

The teams that are breaking through share a few things in common:

They are realistic about what agents can and can’t do today

They start narrow and expand carefully

They invest in the workflow, not just the model itself

So this article is a primer on this. Let’s have a look at what agents are, why they fail, and how to get them to work.

Here is the agenda:

🤖 What is an agent, really? — clearing up the confusion between chatbots, copilots, and agents.

🧱 The building blocks — models, orchestration, and tools: how agents actually work.

🏆 Use cases for agents — patterns from early winners and use cases with real ROI.

🔧 From prototype to production — how to bridge the reliability gap and the compounding errors problem.

Let’s dive in!

I got a lot of help for this piece from Gorka Madariaga and the team at AWS, who work on Amazon Nova and have spent the past year deep in the trenches of enterprise agent deployments. Their perspective on what’s working — and what’s not — was invaluable in shaping this article.

Disclaimer: even though AWS is a partner for this piece, I will only provide my transparent opinion on all practices and tools we cover, Nova included!

🤖 What is an agent, really?

The word “agent” has become one of the most overloaded terms in tech.

Vendors slap it on everything from simple chatbots to fully autonomous systems, which makes it hard to know what we’re talking about.

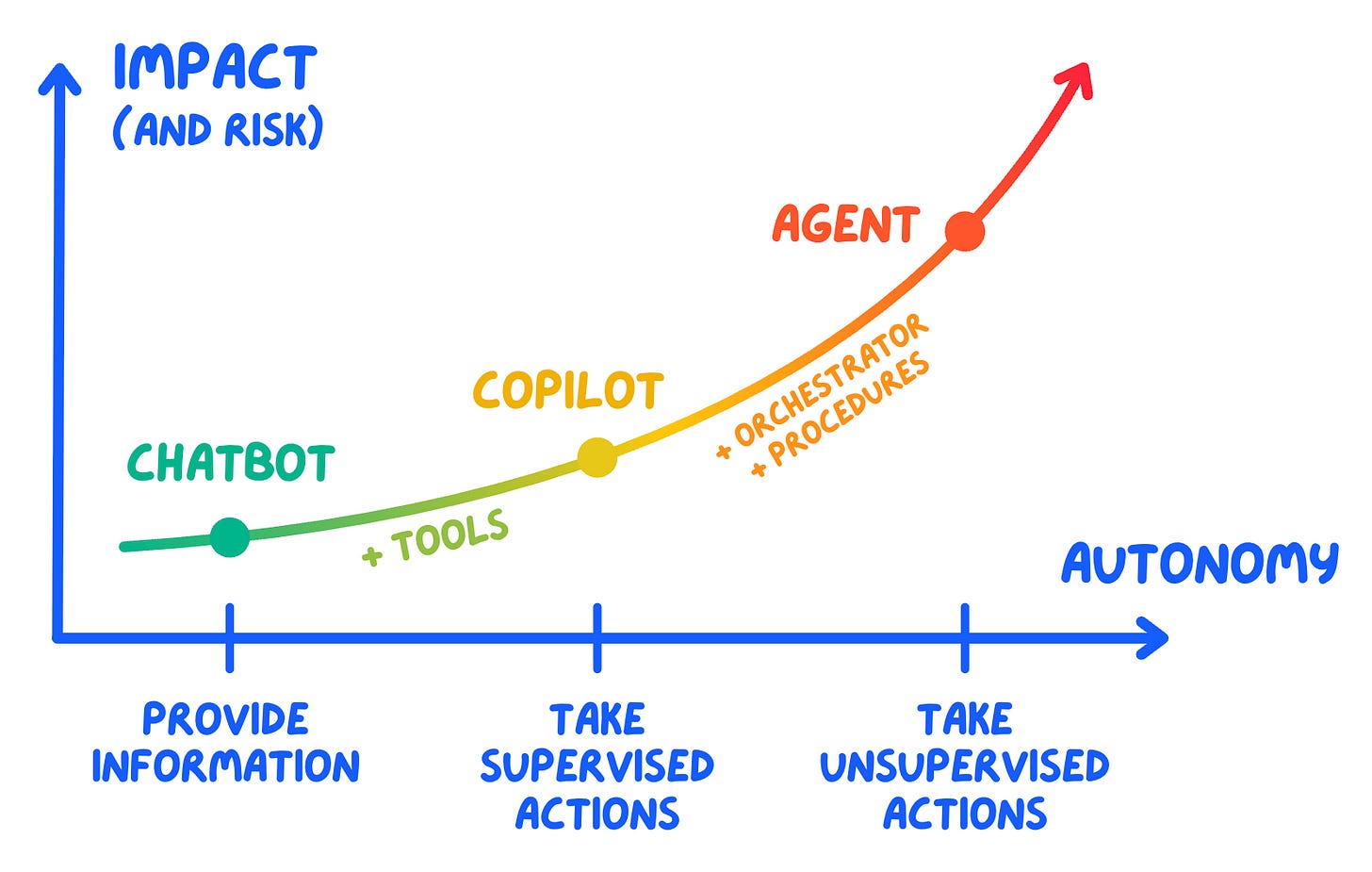

To clear this up, I find it useful to think about AI systems on a spectrum of autonomy:

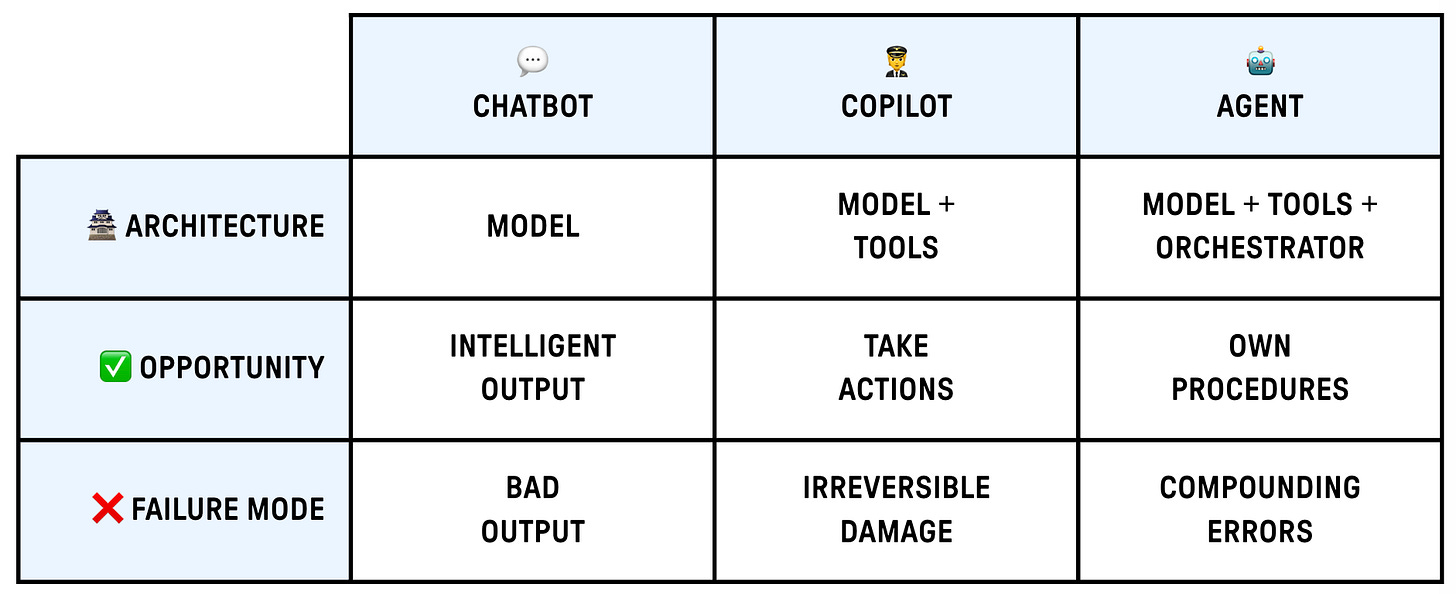

💬 Chatbots — respond to questions. They take an input, generate an output, and that’s it. They possibly keep memory across sessions, but have no ability to take actions. Think classic customer support chat.

🧑✈️ Copilots — assist humans in doing work. They can access context (your codebase, your documents), draft outputs, and take some actions. But a human remains in the loop, reviewing and approving. Think ChatGPT with tools.

🤖 Agents — act autonomously to achieve goals. They can reason, use tools, and plan multi-step workflows without waiting for human approval at every step.

The key distinction is that agents do things autonomously — they don’t just respond. They interact with external systems, make decisions, and take actions that have consequences.

Which makes them both powerful and risky. The feedback loop is fundamentally different because chatbots have a human in the loop all the time, while agents have not.

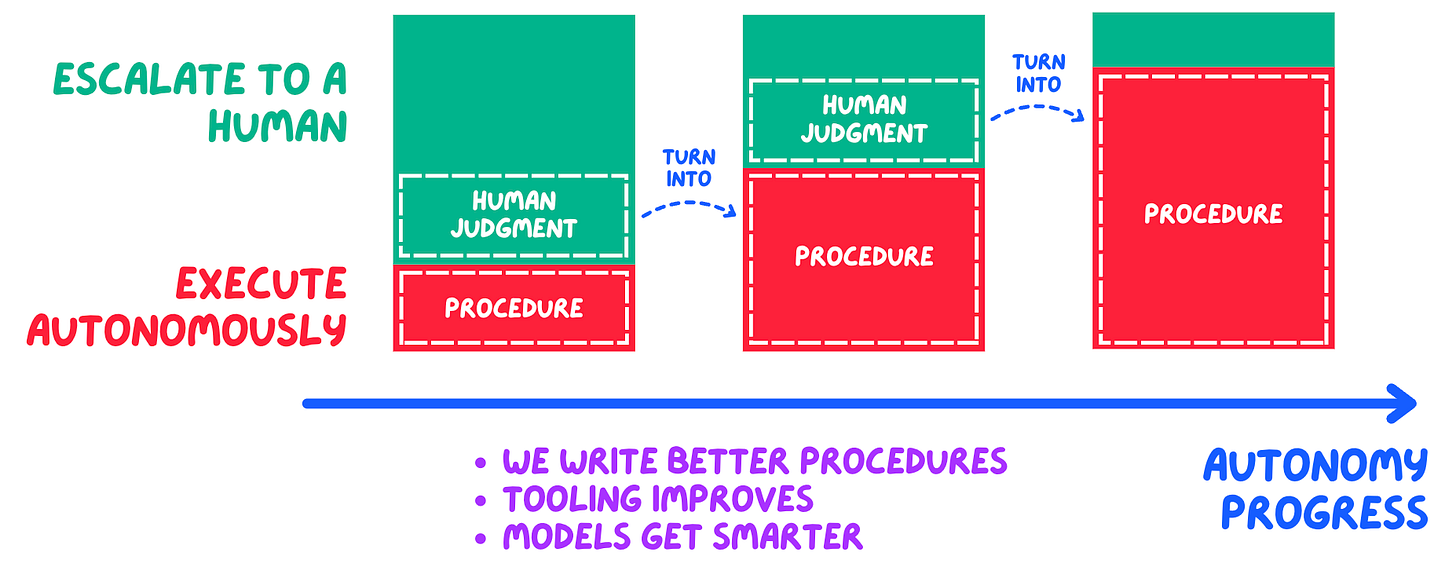

Designing for this is hard, which is the reason why successful deployments usually don’t go full autonomy from day one (or ever). They escalate to humans for high-stakes decisions, and gradually expand the agent’s authority as trust is established.

In other words: the best agents today are only selectively autonomous: independent on routine tasks, supervised on critical ones.

🧱 The building blocks

To understand how to make agents work, we first need to break down what’s inside one. At its highest level, every agent has three components:

🧠 Model — this is the “brain” of the agent. It’s the LLM that does the reasoning: understanding the task, deciding what to do next, and interpreting results. The model is what most people focus on, and it makes sense: a smarter model generally makes better decisions. But there is much more 👇

🔧 Tools — these are the external capabilities the agent can use: APIs, databases, browsers, code execution, file systems. Tools are how agents interact with the world. Without them, you just have a chatbot.

🔀 Orchestrator — this is the control layer that manages the agent’s workflow. It handles things like: breaking a goal into steps, deciding when to call which tool, recovering from errors, and knowing when to stop. Some agents use simple loops, while others use complex state machines or even multiple sub-agents coordinating together.

Some add memory as one of the building blocks. On a semantic level, I kinda disagree with this, as memory doesn’t feel as fundamental as the other three. Model, orchestrator, and tools are all required for any agent to function. Memory is more of an enhancement — many useful agents are stateless within a single task.

Also, technically, memory is often implemented as a tool (e.g., vector database lookup) or managed by the orchestrator (e.g., maintaining conversation state). It’s not a truly separate layer.

But I digress. The point here is that an agent is a full system, not just a model, and the system matters a lot. A better model doesn’t automatically translate into a better agent if you have flaky tools or the orchestrator can’t recover from errors.

🏆 Use cases for agents

Given all of this, where are agents actually delivering value today? This is important to discuss for two reasons:

Many teams legitimately need ideas and inspiration about what to use an agent for.

As of today, it is true that some use cases work better than others. Which ones? And why?

If you have to take only one idea away from this section, it’s that agents that work are most often not trying to be general-purpose assistants that can do anything. They are focused on specific workflows, with clear boundaries, and humans in the loop for edge cases.

About this, the most common area is automation — handling repetitive, multi-step tasks across systems: updating CRMs, processing invoices, syncing data between tools. PwC found that 64% of agent deployments focus on workflow automation.

A notable subset of automation agents is UI automation.

AI is better at using tools and APIs than it is at clicking around websites, but hey, many systems don’t have APIs! Or they do, but they are incomplete and/or painful to use. There are plenty of industries like healthcare, insurance, or travel, whose platforms are often utterly legacy and have never been designed for automation. On these systems, agents that interact with UIs directly, clicking buttons, filling out forms, or navigating pages, can unlock an insane amount of value even by doing relatively simple tasks.

As engineers, we often focus on the exciting and sophisticated, and forget there is still a ton of value in the boring.

About UI automation, allow me a quick plug: this is exactly the problem that the Amazon AGI and AWS teams have been working to solve with Amazon Nova Act. It’s a managed service for building agents that automate browser-based workflows. These include navigating UIs to validate functionality in web QA testing, filling out forms, or extracting data from pages.

I also love their focus on reliability over raw intelligence: Gorka prides that, on early enterprise customer workflows, Nova gets 90%+ reliability, vs an industry average of 60-70%.

So, as of today, successful cases do exist, but they are practical and down-to-earth. They focus on well-defined tasks, their blast radius for errors is contained, and there’s a clear baseline to beat (usually: humans doing boring work manually).

Conversely, what doesn’t work well yet is open-ended agents that require a lot of judgment, long-running autonomous workflows, or anything customer-facing with high stakes. The reliability math just isn’t there.

Here are a couple of successful examples from our community 👇

1) Onboarding

One of the first use cases we’re piloting is an agentic onboarding flow for customers, where the agent automates parts of the activation process.

The goal is simple: scale onboarding capacity while shifting human agents toward higher-value interactions. We’re currently A/B testing this against our regular onboarding flow, and just started validating early data and customer feedback.

— Nithin SS • Head of QA at Lodgify

2) Phone Screening

Our AI Operations Team finished a first version of a phone screening Agent using Telli.

The use case is that at Zenjob we are selecting students for certain temporary/short term jobs and for some cases where we need more comittment from them AI Agents do a phone screening interview call + some assessment is also done.

It’s still fine-tuned but recently the team integrated it into Retool Dashboard for our Operators Team.

— Ferit Topcu • Engineering Manager at Zenjob

🔧 From prototype to production

Once you understand how an agent works, and pick a reasonable use case for it, it can still be a long journey from patching together a small prototype to running something that works (and delivers value) in production.

To get there, here are the things you need to pay attention to:

1) Compounding errors 📉

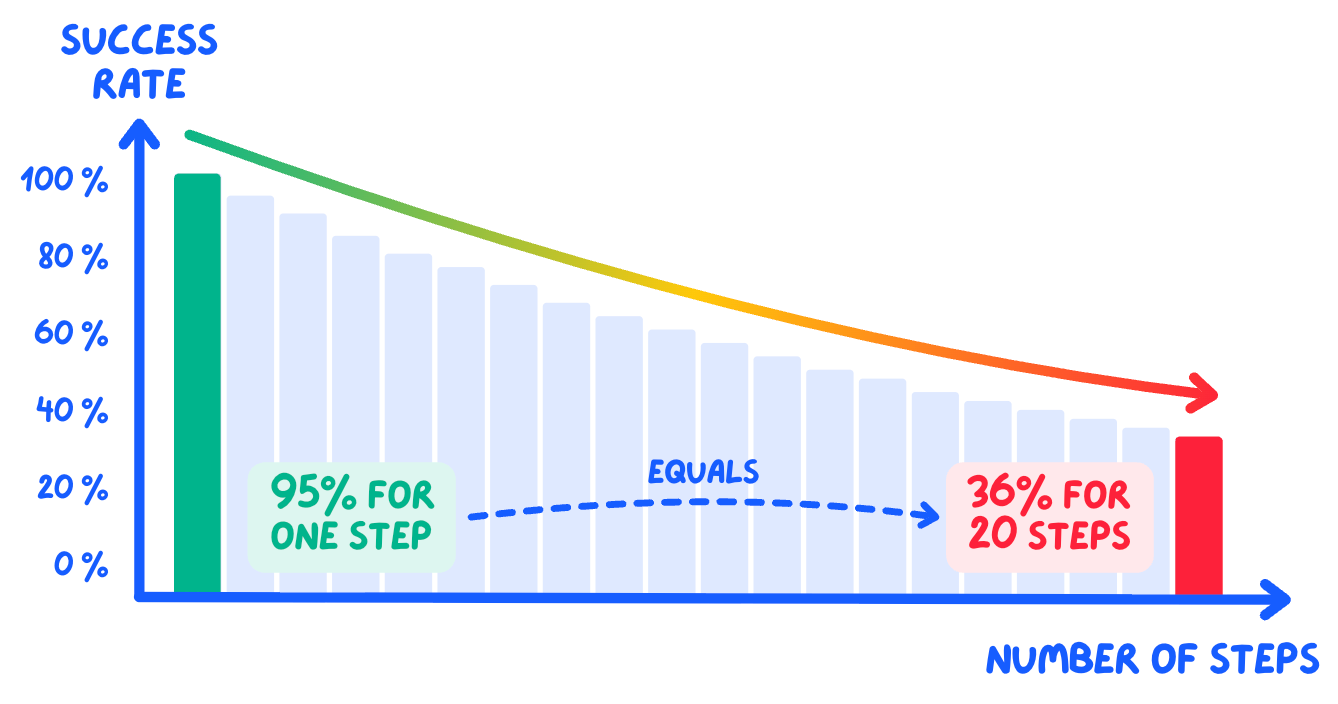

In my experience, this is the most fundamental problem. In any multi-step workflow, small error rates at each step multiply into large failure rates overall.

Quick math: if each step in an agent workflow has 95% reliability (which is optimistic) — then over 20 steps you’re left with just 36% success 👇

This is also why demos look so good: they are short and show the happy path, maybe 3-5 steps, carefully chosen.

The way you counter this is:

Start small — as said above, pick a single, well-defined use case with clear success criteria. Design a small number of steps and make each one as easy as possible.

Design for human-in-the-loop — what decisions can the agent make alone? What requires approval? A simple heuristic: if the action is reversible and low-cost, let the agent proceed. If it’s irreversible or high-stakes—like sending money, deleting data, or external comms—require human approval. Build escalation paths into the workflow from day one to cap risk and reduce errors on difficult steps.

Treat reliability as the key metric — focus on the percentage of tasks completed successfully. Evaluate and iterate all the time!

2) Testing and debugging 🔬

As we all know, agents are non-deterministic: the same input can produce different outputs across runs. This means you can’t write traditional tests with the same confidence you’d have for regular software. When something fails, it’s hard to reproduce.

For this reason, you should invest in observability early on, so you can see what the agent is doing, step by step.

Concretely: log each step’s inputs, outputs, and latency. This advice is frankly good for any software, but especially non-deterministic one. Tools like LangSmith, Langfuse, or even structured logging can help. The goal is a full trace from trigger to completion.

3) Account for scale 📈

Deploying agents even at a moderate scale requires taking into account many factors:

Authentication — how can the agent act properly on behalf of users across systems?

Security — are you sure the agent can’t access things it shouldn’t?

Escalation — does the agent know when it needs to pause and escalate to a human?

Latency and cost — are you accounting for volume? In the LLM world, everything compounds fast.

Reflect on all the ways your production environment, with real users and real scale, is different from your confined developer environment.

4) Buy vs build 💳

Finally, consider the buy vs build tradeoffs, and keep a bias for buying everything that’s not core to your product.

Building agent infrastructure from scratch—orchestration, tool integrations, deployment pipelines, monitoring—can be a massive undertaking. If it’s not going to be strategic IP, it makes sense to use managed platforms that handle part of the complexity, so your team can focus on the actual business logic.

The options range widely:

For UI automation specifically, Amazon Nova Act provides a managed service that handles the infrastructure complexity and scales seamlessly to production workloads.

For no-code workflow automation, platforms like Lindy, n8n, or Zapier Agents let you build agents without writing code.

If you want to build in-house with full control, frameworks like LangChain and CrewAI give you the building blocks to create custom agents from scratch.

📌 Bottom Line

And that’s it for today! Here are the main takeaways:

🤖 Agents act, they don’t just respond — The key distinction from chatbots and copilots is that agents take actions with real consequences. This makes them powerful but also risky.

🧱 Focus on the system, not just the model — An agent is made of three parts: the model (brain), the orchestrator (control layer), and the tools (how it acts). Vertical integration across all three is what makes agents reliable.

📉 Compounding errors are the killer — At 95% reliability per step, a 20-step workflow succeeds only 36% of the time. This is why demos look great but production fails—demos are short, production workflows are long.

🎯 Start narrow and specific — The agents that work today aren’t general-purpose. They’re focused on well-defined workflows like invoice processing, CRM updates, or UI automation where APIs don’t exist.

👥 Design human-in-the-loop from day one — Keep humans supervising high-stakes decisions. Agents should be selectively autonomous: independent on routine tasks, supervised on critical ones.

🔬 Invest in observability early — You need to see what the agent is doing, step by step. Log inputs, outputs, and latency to debug non-deterministic systems effectively.

💳 Buy the hard parts — Building orchestration, deployment, and monitoring from scratch is a massive undertaking. Use managed platforms so you can focus on the workflow logic specific to your business.

A special thanks to Gorka Madariaga and the AWS team for partnering on this piece and providing expertise and and insights. They recently presented a lot of new functionality at re:Invent, so I am linking below a few sessions if you want to learn more:

If you want to learn more about what they’re building with Amazon Nova, check out their work at aws.amazon.com/nova/

See you next week!

Sincerely 👋

Luca

I like this pragmatic approach to releasing agents to production. I also fully agree with having observability in place at the start.

Observability early is such a critical point, you can’t debug what you can’t see.