About four years ago, I published an article about generalists which was part advice part self-therapy.

In fact, having been a founder for most of my career, I have a love/hate relationship with my skills:

I love doing—and learning—many different things.

I dread not being capable of top-notch execution on pretty much anything I do.

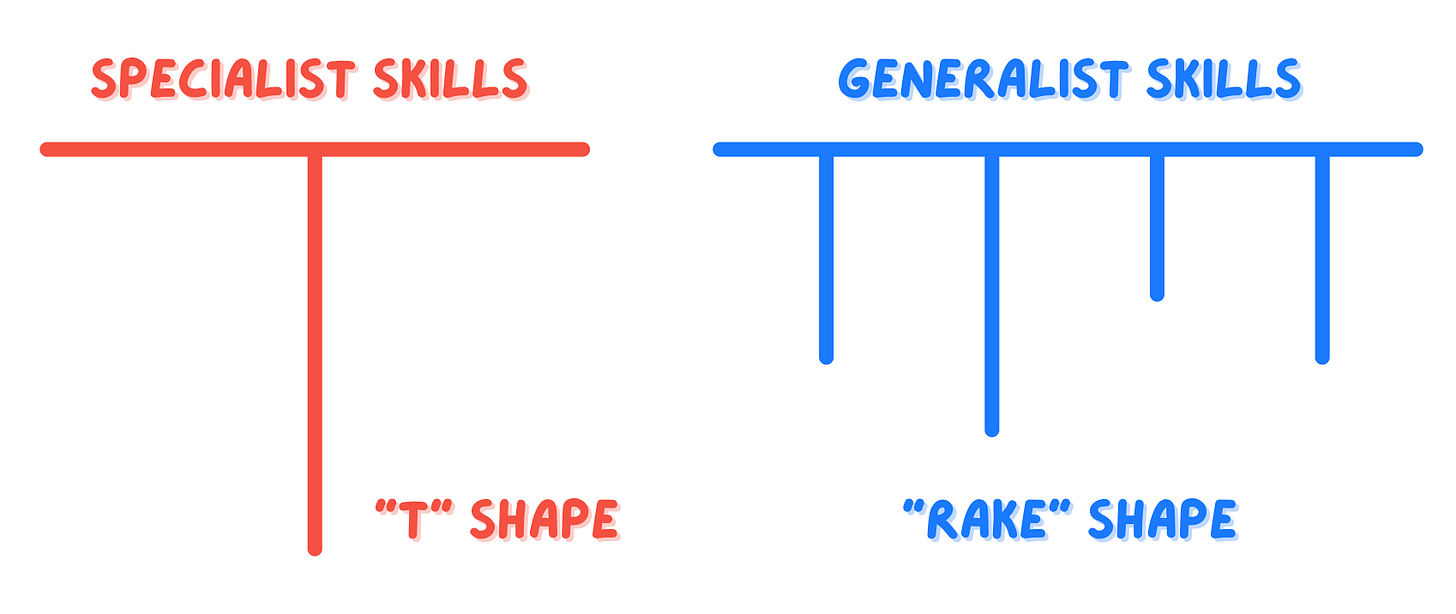

In the industry we are fond of saying we should balance our specialist and generalist sides by building a T-shape, that is: solid foundations across the board + one strong specialty.

We also often hear that it is good to build the horizontal leg during the first years of your career, before specializing into something. This is good advice! But it also sounds kind of like: go on and play with things for a few years, but then get your sh*t together and figure out what you want to do as a grown up.

Many people do indeed, but some don’t, and end up with shapes that look more like a rake, with various vertical legs of odd, different lengths, protruding from the horizontal base.

This is old news and, by now, we shouldn’t overly worry about it. There is plenty of data out there about how generalists eventually do very well in their careers, and above all I am fond of Range, by David Epstein, which basically reads like an ode to generalists.

However, this reassurance never felt completely satisfactory to me.

My rampant impostor syndrome has often demanded more, which is why I wrote the previous article in the first place — to address how generalists actually fit into software organizations, and how they should think about themselves.

Fast forward four years, and I think it’s time for an updated take, largely because of AI. It is no secret that lately I have been writing a lot about this, and one angle I am particularly interested by is how AI is changing what skills are relevant, and how teams are going to change because of it. Of course it’s still early to say, but some trends are already in place, and I think it’s worth talking about them.

So here is the agenda for today:

❓ What is a generalist? — as always, definitions first.

🎨 Product engineers — the rising stars of generalists.

🎽 Engineering managers — a classic destination which still 100% stands today.

🏗️ Staff+ engineers — growing your generalist career as an IC, a surprisingly viable option.

🏛️ Applying your domain knowledge — attacking the problem from another angle.

Let’s dive in!

❓ What is a generalist?

Generalists come from all walks of life, and it’s hard to find a proper definition of what makes for a generalist. I asked some friends about why they thought they were generalists, and here are some of the most common answers:

You are equally (or similarly) proficient in various non-overlapping skills.

When looking at openings, you can apply for roles that belong to different career tracks.

During your work, you regularly perform tasks that usually fall into the domain of different specific roles.

The problem is these things exist on a spectrum. Full-stack engineers may feel like generalists themselves, but they are arguably less so than a good friend of mine who started their career as a pre-school teacher, turned into a customer success operator, QA engineer, and eventually engineering manager.

There is also this common notion that people end up generalists largely because of accidental twists and turns in their careers. It may be the case for some, but I don’t think it’s how it happens for most.

We follow our inclinations more than we realize, and, as Steve Jobs said, often times you can only connect the dots backwards, and see that your journey makes sense in a way that you didn’t realize yourself. So, I have known a lot of generalists, and here is an observation: the vast majority of them are motivated by the what, rather than the how. They are motivated by the impact and the value they create, rather than building stuff for the sake of it.

For the sake of clarity: I have also known a lot of people motivated by the how—by doing things well—and they are super valuable. They just happen to turn more often into specialists.

Another interesting angle goes back to Daniel Pink’s model about motivation — which I have probably quoted in the newsletter more than any other mental model. Pink believes our motivation depends on three factors: Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose. In real-world situations, these are often at odds, especially autonomy and mastery. Being more autonomous requires being able to do more things, which naturally creates a tension with the level of mastery you are able to achieve in each domain.

Now, autonomy and mastery might be at odds, but impact and mastery are not, or should not be. In fact, in healthy teams impact comes first, while mastery is subordinate to it.

This is true at all levels, and even in your career as a whole. With the exception (maybe) of the few initial years of their career, people get largely promoted because of the impact they produce, rather than the skills they possess. And on your resume, what you helped accomplish always speaks for your skills more than anything else you can put in there.

Now, I feel a big difference between generalists and specialists is that this mindset comes easy-ish to the former, while the latter need to come to terms with it. In fact, if we value ourselves, as professionals, by the level of quality, complexity, and sophistication of the software systems we create, we might be disappointed e.g. to take a design shortcut to improve the time to market, at the expense of some tech debt down the line.

Now, how does all of this apply to modern tech teams? Let’s look at various roles and angles: